Chelsea Hogue

Bob is Missing

Bob is missing. Bob isn’t inside that man anymore. Sometimes when Edy comes by for a coffee and a visit, he does a good job of looking at her; but on most days he stares down at his feet or busies himself with something in his kitchen, or office, or anything from the outside because something always needs to be fixed and like a good post-bronze age man, he believes he’s just the one to do it.

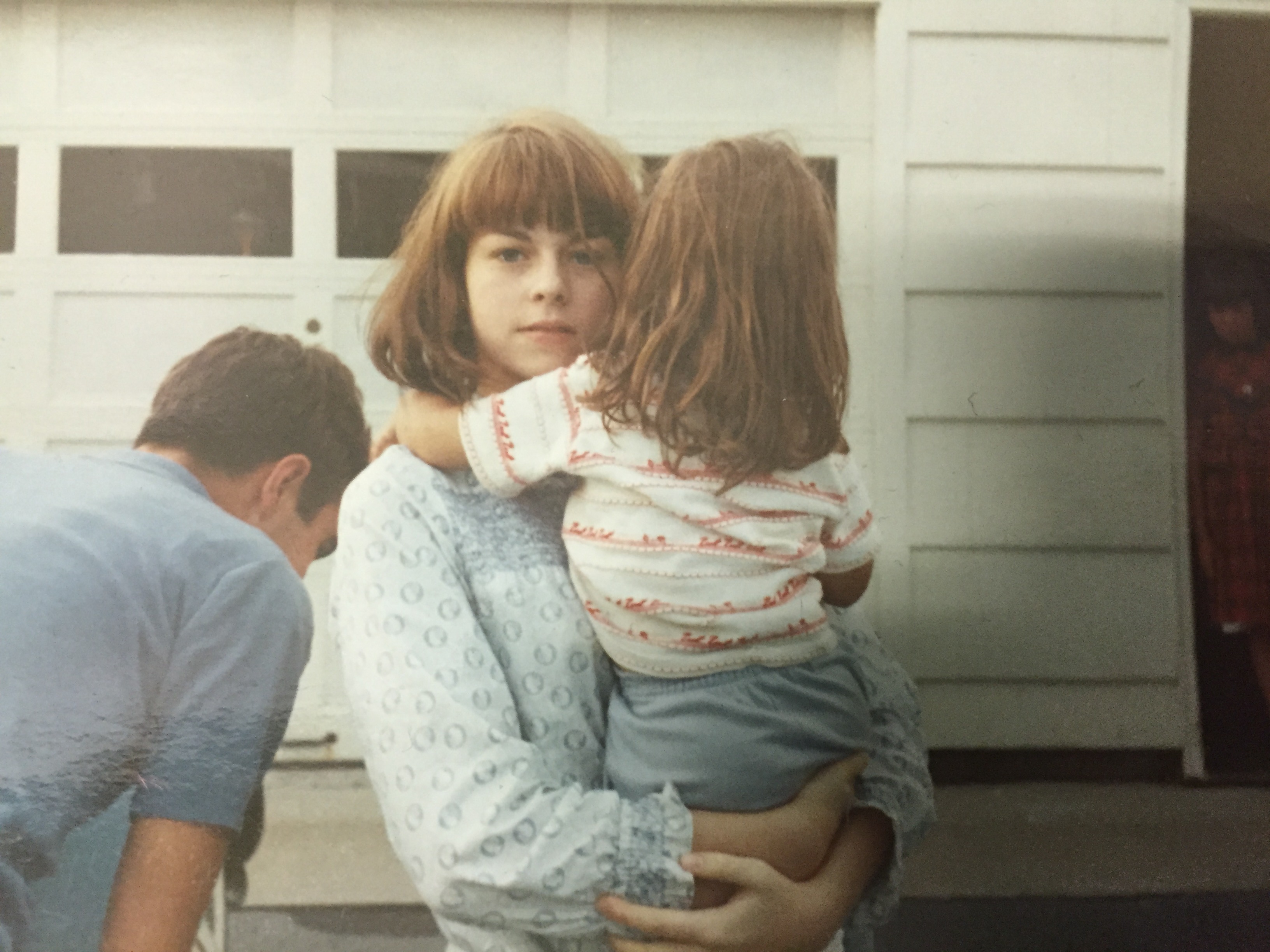

We never grow weary of seeing a mother hold her child, or any woman hold any child, or even to see a child hold a child. Diane Arbus’ photo, “Woman carrying a child in Central Park, NYC,” 1956: a perfectly coiffed white woman in dark lipstick, whose eyes we cannot see—she is beautiful in relation to that she whispers rather than announces the breathlessness we feel after turning into the camera and having our photo taken before we’re able to know it. She carries a sleeping, bundled baby, resting near her breast. A professionally dressed woman of the 1950’s who has a place to be but isn’t there yet. Soapy secretary cum celestial Madonna and babe. There is nothing carnivalesque, nothing particularly shrewd or distinctly Arbus in this photo—but there is an imperative in her non-arrival: we’ve caught her mid-motion; we’ve interrupted a commute—and it’s true that every woman cradling a child ought to be, if she isn’t already there, walking toward hearth and home.

At home is Bob’s broken toaster, which scorches one side of the bread and leaves the other side soft and cold. A vacuum cleaner returning last month’s dirt. Bob shakes out a tarp on the driveway and spreads out the vacuum’s parts on it so that they’re lined up in neat rows. Edy stands over him, dumbly, holding the two screws he needs next, looking at the back of his skull, his hair graying by sprigs at the temples, the small thinning circle centered on his crown, as he bends over all the parts, which only distantly make sense when not put together. His shirt’s a blendable blue, statically charged, sticking to his skin in the right and wrong places. It’s a blue that’s for everything, blue for hot fire, blue, blue for held breath, blue for bruise, blue for cold fingers. With a child’s blue marker only one underlined passage in Hélène Cixous’ Dream I Tell You:

“…you reader-spectator are aware of this but you forget what you know so you can be charmed and taken in. You connive in your own trickery. You pull the wool over your own eyes. The thinner the razor blade that slips between you and yourself is an imperceptible vertical hyphen.”

Which could all be shortened to the very next sentence: “You are a you.” Naturally, and we’ll know it when we see it, and believe it when we see it, but that doesn’t make a single image any easier to understand, does it? Blue comes onto Bob, it comes onto a page, too—it isn’t possible for us to lighten the objects to which colors append themselves.

Sometimes Edy believes Bob would rather be more like her, living lonely but not alone; and sometimes she believes that he would rather be more like himself, living lonely and alone. She puts the screws in his hand and her eldest daughter pouts in the shade of the garage door. She chews pieces of tinfoil to tiny nothings and spits them out like bullets. She wanted ham and maraschino cherries for breakfast; she has also, in her short life, eaten a handful of cigarette butts out of an ashtray and swallowed. She’s unreasonable and it’s on purpose, but she won’t tell anyone why; that would undermine all the effort it takes. Edy told her that if Joan of Arc could lead a nation to war at the age of 17, disguised as a boy, then she could be a bit more understanding. One must play the system with a tucked-in lip. That’s the second or third thing.

Edy picks up her youngest with one arm. They’ve mastered the most elegant dance without a good name. When holding the child, she can’t see beyond the right angle created by the child’s neck and shoulder; it’s her only small scope of see-space. Edy begins to feel that Bob’s not looking at them may be best, because most of the time, when he does look at her, he gets that pained expression in his eyes; he looks at her hairline, or the very tip of her cheekbone—and while she expects this, she never fails to feel confused by it.

And even worse, on rare occasions, when he does finally look at her, long and hard, after a significant break, he covers his tragic mouth with his hand, to hide his distaste for her, she thinks, or to keep from crying out for her help or crying out in anger. It saddens her terribly. Not for her, but for him. She always loved and wanted to take good care of Bob, probably as much as he loved and wanted to take good care of himself. What she had been interpreting as affection, she now thinks could have been guilt—because maybe they are one in the same and, after some time, it’s impossible to know the difference.

When the painter Théodore Géricault wanted art to get a bit realer while finishing what would become the icon of French Romanticism, The Raft of the Medusa, he spent years down in the morgue, drawing the heads of France’s guillotine victims before finally reconstructing the mangled raft in his studio—the ripped sails and splintering boards—and bringing the dead bodies home with him each week, so he could position and re-position his putrid models. A single horizontal diagonal rhythm forcibly shifts our eyes from the good as dead at the bottom left of the painting up to the living reaching for the nirvana of survival. In one image: tragedy has a baby and it’s exaltation, or: loss to love—and there’s nothing more romantic than that.

And, of course, it is like this: the same fingers which once held the shepherd’s staff are now gagging the sheep dog. Bob asks Edy a question she can’t hear; however, the question still floods her mind and she starts noticing things, small things, everything—all the little things that she wishes she wouldn’t or somehow couldn’t. Bob is the spectacle and she’s the spectator; in her trance, she is not free. She cannot look away. She feeds Bob tiny hamburger patties, one after the other, patty after patty, and watches him eat in the hyper-distilled quiet until he is sick, until crumbles of silvery meat are clinging to his greasy chin, a hulking lump stuck inside his bottom lip and he can’t get it out but to swallow.

Chelsea Hogue is a writer living in Northampton, MA. She’s working on a collection of stories based on the photos she’s bought off ebay. You can find her online at chelseahogue.tumblr.com

Chelsea Hogue is a writer living in Northampton, MA. She’s working on a collection of stories based on the photos she’s bought off ebay. You can find her online at chelseahogue.tumblr.com