Samantha Memi

The Greatest Mystery

The world is full of mystery. Philosophers for millennia have wondered why so much on this Earth is inexplicable. In 2011 UNESCO called an international conference to discover which of the world’s mysteries is the most puzzling. After two years of investigation, the historians, scientists and theologians concluded that the strangest event in the history of the world was the love affair between Orson Welles and Louise de Vilmorin. No intelligent member of this august body could understand why Louise, whimsical, elegant and replete with insight into love, would want to spend even a moment of her life with the pudgy Mr Welles.

I read about the conference in the Journal of Inexplicable Phenomena, and realised the mystery of this famous couple would be ideal material for my research into the behavioural patterns of celebrities in the mid-20th century. I also realised that solving the world’s greatest mystery would bring wealth and fame, and for this reason I decided to investigate the matter.

The only explanation I could surmise for Louise being attracted to Mr Welles was that she suffered from chronic myopia. This turned out to be untrue. I therefore turned my attention to Orson, and I was surprised to discover how many people who had known him would mention his resemblance to a Cornish pasty. Was this the key to the mystery? Was Louise de Vilmorin an ardent fan of the Cornish delicacy?

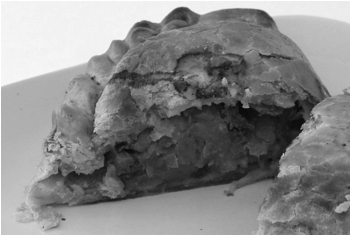

If you don’t know what a Cornish pasty is, here is a picture of one:

And here is a picture of Orson Welles when he was young:

Many will say he looks nothing like a Cornish pasty; the pasty has a natural flamboyant air, whereas Mr Welles is a sycophantic looking creature, seemingly without truth or humility in his life. But I quickly understood what his friends and acquaintances had noticed. As with so many mysteries, it is necessary to look beneath the surface. The interior of a Cornish pasty is vegetables, mainly carrots, potatoes and peas, mixed with subtle herbs and spices to give a flavour of the countryside. So obviously there is nothing of the Orsons in that. But factory bought pasties – and Mr Welles is a very much a factory-made product – have large amounts of artificial flavourings, colourings and preservatives. The factory pasty may appear debonair and light-hearted, but at its centre is a welter of sodium metabisulphite and sulphur dioxide. It is within these flavourless iniquities that the Orson of whom I speak can be discerned.

My attempts at researching the link between Cornish pasties and Orson Welles were fraught with difficulty. Pie factories closed their doors to me as soon as I mentioned his name, and Hollywood was similarly disinclined when I mentioned the words Cornish pasty.

I realised the only way I could get answers to this problem would be to ask Louise herself. As she had been dead for many years I couldn’t phone or email, so I went to see my favourite medium, Madame Zourastía.

—Samantha, she exclaimed when she opened the door to her salon, —how delightful to see you. Come in. Isn’t it a lovely evening. Would you care for a glass of mint tea?

—Yes please.

—How can I help you today?

—I want to speak to Louise de Vilmorin.

—Ah, French. Does she speak English?

—Oh dear, I hadn’t thought of that. I imagine she must do. She was very well educated.

—If not, we’ll have to use an interpreter. Would you prefer someone living or dead?

—I don’t mind.

She gave me my mint tea and I sipped it and found it too sweet. We sat either side of a large mahogany table.

—What was the question you wanted to ask Louise?

—Why did she go out with Orson Welles?

—Presumably, because she liked him.

—Most people compared him to a Cornish pasty.

—Different women have different tastes in men.

—But have you seen him in the film where he steps out of the shadow of a doorway and he’s like a plump overgrown schoolboy with a smirk on his face like he’s got indigestion. Could you imagine sleeping with that?

—Hm. I see what you mean. I’ll ask her.

She waved her arms over the table and green smoke rose up from nowhere. In a husky voice she uttered, —Louise de Vilmorin: are you there?

—I am here.

Coo, I thought, that was quick, and her English had a faint Welsh accent which made her sound ever so friendly.

—Samantha wants to know why you had an affair with Orson Welles.

—Ah, Orson, the Cornish pasty. Well, we met in Paris. It was at a party given by – oh, what was his name? Tall guy, American. You won’t know him; he’s been dead for 50 years. Anyway I’d been invited by my dear friend, Mignonette, who bred poodles, and made quite a good living from it too, and she introduced me to Dai Williams, who apparently was a friend of Dylan Thomas who wasn’t there, and Dai said, —Do you like Cornish pasties?

I thought Cornish Pasties? Who’s he? And, as I was wondering who Cornish Pasties could be, Orson Welles turned up, and asked, —Louise de Vilmorin?

—Yes, I said. —Cornish?

And he replied, —Don’t mind if I do.

And he swept me onto the dancefloor to step the light fandango. Little did I know the music they were playing was the Cornish tango, and little did he know I thought his name was Cornish. So we were off to a confusing start, which neither of us realised for many days.

The party was in aid of the Cornish tin miners who were on strike for better conditions and pay. The host of the party – the American, whose name evades me – came from a long line of solid Cornishmen who had travelled to the US at the end of the 19th century to escape the poverty and toil of the Cornish tin mines, and he wanted to introduce Cornish culture to the Parisien elite, so, as well as the vol-au-vent, canapes, and tarte au framboise, there were heaps of Cornish pasties which unfortunately no one wanted to eat.

We danced and then we sat down, gay and laughing. Dai brought a platter of Cornish pasties. But the one I chose stuck in my throat and I couldn’t manage even half of it. But Orson, the greedy piggy, ate one after the other till the plate was empty.

As we left the party he stole all the remaining pasties and put them in a big sack. No one seemed to mind.

At that time I was very poor, struggling with my first novel, and living in a dreadful slum. Orson, a struggling film director, at least had a nice apartment, so I went to stay with him. As we had no money we dined on Cornish pasties for two or three days. Which, as you can imagine made me rather ill. Unfortunately the effect of eating too many pasties was even worse for Orson; they altered both his appearance and his demeanour. He became stodgy like a pig, and gloomy, without the lightheartedness he had had when I met him. His friends would come round and say, Orson, what’s happened? You look like a Cornish pasty?

We lived together for a few months. And I have to say the first weeks were happy and gay, as all love affairs should be, but eventually his penchant for Cornish pasties became too much for the relationship to bear.

As he became more bloated our arguments grew in severity. The finale came after a blazing row over a Cornish pasty which I had bought from the market and apparently contained too much potato and not enough of anything else. In a rage Orson tore up a film script he had written about a Cornish pasty chef, and rushed out the door, leaving me with rent arrears. The next thing I heard he had returned to the US, and we never spoke again.

Many years later I saw a picture of him in Movies Monthly. I didn’t recognise him at first. I thought, What’s a picture of a Cornish pasty doing in a film review, and then, when I realised who it was, I couldn’t help but imagine hugging him and feeling the potatoes and peas squeeze inside him. Nostalgia does that to one, I suppose. My life’s great disappointment was that he had never appreciated my wonderful crêpes.

I often wonder how different our lives would have been if the host at the party had been Italian, and instead of pasties had imported pizza into Paris. Would Orson and I have had a happier life together? Who knows? It would certainly have been more colourful.

At that moment Louise de Vilmorin faded without even saying goodbye.

—Well, said Madame Zourastía, —it would seem that you were right about your analogy between Orson Welles and a Cornish pasty.

—I find it sad that my beloved Louise de Vilmorin would shack up with Orson Welles.

—Apparently he had a nice apartment.

—I don’t understand why she said she was poor. She came from a very rich family.

—But my dear, said Madame Zourastía, —being dead doesn’t exclude you from being dishonest.

My God, I thought, if you can’t believe the dead, who can you believe.

I crossed her palm with silver (courtesy of Visa) and made my way home. I was upset that Louise had moved in with Orson simply to have somewhere nice to live, but who am I to judge. Would I think better of her if she had gone off with Buñuel or Picasso. I should be grateful she had helped me solve the greatest mystery known to civilisation. The world’s cultural historians would forever be in my debt. I would be remembered in the history books. Samantha Memi, the researcher – no, the brilliant researcher – who explained the mystery of what had happened between Orson Welles and the seductive Louise de Vilmorin.

Note: this story is untrue. Cornish pasties are made with beef, potatoes and swede but, as I am vegetarian and have an antipathy to swede, I changed the recipe.

Samantha Memi lives in London. She is the author of the chapbook Kate Moss & Other Heroines. Her stories have appeared in Fiction International, Birkensnake, and The Cortland Review. http://samanthamemi.net.