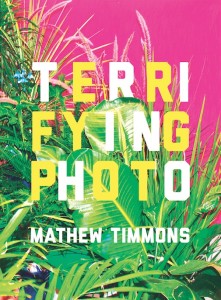

Terrifying Photo by Mathew Timmons

a review by Aaron Beasley

Wonder

2015

241 pages

$19.95

How do you read a poem? The literal-minded might say, “Just let your eye light on it”; but there is more to poetry than meets the eye.

This is how one generic literature textbook introduces college students to the study of poetry. Reading begins in mystery, façade, surfaces conjuring an ever-beyond depth. Which can be unsettling, even terrifying! Barthes could turn out the lights on this ideological shadow play, but the mirrors? What about the curtain? the veil? the screen? Wait—what?

There is more to Mathew Timmons’ TERRIFYING PHOTO than meets the eye, as Holly Myers in her introductory interview warns that the referent “PHOTO” of the book’s title in fact “doesn’t appear in the text at all.” The eponymous piece—center stage in this chronological selection of Timmons’ written, published and performed works from 2005 to 2014—does have a readily found source image, but I won’t spoil the joy-pain-lol-shame-hilarity-ew-terror of reading its catalogue of public reactions, presented wholesale (almost) in their original (not quite) sequence of online comment streams:

Messedupotamia eeewwwwwwwwwwwwwwwwww!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

Ewwwww…. GROSS Can you bleach your eyeballs?

eeeewwwwweeeee!!! Ewwww… “THREW”?! as in “UP”?!! ‘Cause I sure

did…. excuse me---must vomit now. barfed after i shared it.”

This form of excess conceals the mystery connected with it. By withholding the visual impetus, the piece shews its panoply of automated critique like a readymade collage sampled from the familiarizing disorder of performative usership (“There is so much wrong with this picture I can’t even begin.”). Posing as a kind of screen for violent truth, language substitutes its appearance of solutions for the insoluble. We may just as well read the effusive commentary-turned-spectacle as what three of the four reporters in “Good News! Good News!” (performed by Jay Erker and Michael Anthony Ibarra, featured in PHOTO) call “a kind of post-modern greek chorus offering my snarky opinion on whatever crisis my human counterparts find themselves in.”

The my here is key as Timmons keeps his subject pronouns in protean shipshape-shift with pieces titled “They,” “We Are,” “I Wonder About Shit,” as well as a three-part plurimedial work (with text, slide lecture, and improvised song versions) named “Just For You,” returning the organized mess of structural chaos to the world-weary word itself: language that in its objectifying address to a given speaker-hearer always-already activates a polysemous misidentification:

I’ll terrorise, publicise, capitalise, mesmerise,

idolise, wave goodbyes to all the things you despise.

Just for you. Just for you.

Timmons’ most hypnotic written work (especially when performed) engages this appeal to the always-uncountable reader-viewer-listener, a figure inevitably isolated and inundated by the second-personal pronoun’s singular duplicity. The affirmed presence of this rarefied-ubiquitous other essentially gives place to poetic utterance, and vice versa. Take “Encouraging Words” (not featured in PHOTO), a compulsory participation-performance-poem in which the audience, constrained by that special politeness (and polity) common to poetry readings, receives a torrent of exquisitely glib, one-size-fits-all imperatives culled from fitness videos. Discarding the uplifting, ever-redemptive (because always-resurgent) norms of poet-voice, Timmons turns the tenor of inflective lyricism back upon his audience, cheer-shouting their reposeful histrionics of passive spectatorship, “come on! come on!” unto a defamiliarizing exuberance (note the recording’s lack of audible mm‘s), demanding “breathe! breathe! let’s go! goodgoodgoodgood very good!” until “there it is!” the genre of public readings as such “keep it up!” makes its way “on to the next level!!”

I won’t pretend to know Timmons’ exact aim here, but one effect of this collective appeal to personal advocacy seems to tie the cruel logic of privatized lyric intimacy—always demanding a public venue—to the absurd rationalism of commoditized workout culture—as in Let’s find a fitness routine tailored to our discrete health objectives and then pay a trained expert to yell things at us! Echo chambers abound; “everybody’s gotta start somewhere, and the wall’s a great place to start!”

But the poet acquaints themselves with duplicity at x’s own peril, representation being ideology’s favorite game. “A spectacle,” so Simone de Beauvoir, “by definition, can never coincide with either the inwardness of consciousness or the opacity of the flesh.” As the faux news anchors (Erker and Ibarra) report by turns, “The disparity between reality/ and what is depicted in the media./ And whether or not the image/ provided by the media is actually more/ real to the masses than the ‘real’/ reality,” they impart, post-post-ironically, “Just think about it for a while…” What emerges in that to before the masses (and prepositionally from the Greek phos- “light” to -graph “writing”) makes all the perceptual (and factual) difference, if Guy Debord is believed: “In a world which really is topsy-turvy, the true is a moment of the false.” Truth is beauty, beauty exuberance. Lionel Richie, via Timmons: “Life was all cake and ice cream/ Truth was true/ And lies were lies”

TERRIFYING PHOTO trades in spectacle’s shimmering monopoly of appearance with all parodic-seriousness, corroborating Debord’s conviction that whenever one analyzes spectacle, “one speaks, to some extent, the language of the spectacular itself in the sense that one moves through the methodological terrain of the very society which expresses itself in the spectacle.” This becomes apparent if-when the reader identifies with the textual addressee (“Just let your eye light on it”), blindingly hailed within the “spare” “excess” “abundant” “immoderate” “overactive” “unproductive” “fecundating” “tasteless” “supererogatory” “supervacaneous” “puffy” “surfeit” “nimiety” of voices: you becomes the vanishing point of poetic action. Timmons: “This is a place created just for you. A place just for you to be relaxed and comfortable. Just for you to feel good as you, [Your Name Here], in this special place.” If we say with Judith Butleri, in Excitable Speech, that language “is a name for our doing,” denoting both “‘what’ we do” and “that which we effect,” well, Vous est un soi.

But this is not mere linguistic experiment for its own sake, nor some elaboration of socially disengaged, purely formal techniques of poetic making. Despite recent claims of separability (and outraged responses that, in the heat of righteous anger, continue to suggest the notion rather than undermine it), aesthetic considerations tend to be so boundlessly political that we in fact hardly recognize them as such—and vice versa. The trouble isn’t whether but how often we forget that the inverse of this statement is equally if not more true. Timmons, in another key,

With the constantly circulating dialectic between order and disorder,

elements of disorder can increase the level of information produced in a

complex system, bringing out a relationship between the elemental

disorder of entropy and the ‘meaning’ of creativity.14

The confusion of ‘democracy’ and ‘anarchy’ is common enough,

especially among Americans; indeed, I myself might be accused of adding

to the overall amount of critical entropy with this very essay.14

But back to our initial question, How do you read a poem?