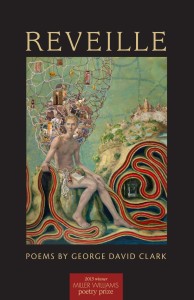

Reveille by George David Clark

a review by Michael Lavers

The University of Arkansas Press

2015

Between deep sleep and total wakefulness there is that winding, mossy way through which Keats chased his nightingale, a darkness fringed by flower scents and fays. This is the hour of Reveille, the debut poetry collection from George David Clark. If this book is a wake-up call, then it’s a wary one, its “whisper-weight trumpets of light” too taken with the dream to break it, too hushed to toll us back to anything resembling our sole selves.

A kind of sleepy rapture is the book’s best mode, “what we might foolishly / call a slumber but is in fact a kind of distant prayer.” Such stillness leads to visions of what we otherwise might overlook. We’re shown the sepias of peahens, “eggplant-grays,” the mass of nothingness inside a well, “its pillar / of shadow, this gossamer obelisk / built to dissolve.”

But the best of these poems don’t dissolve. They’re built to last. Their strength comes from an alchemy of opposites (day/night, sleep/wakefulness, imagination/reality, silence/sound) in which Clark has it both ways, recording “the sound of the self” and “the self’s deletion” in lexicons both plain—“It reminds him of a concert he attended / in high school”—and lush: “polite in genteel villas, / I jawed with chatelaines in jaguar / boots and mufflers of chinchilla.”

Perhaps the best single poem is “Reveille on a Silent Whistle,” one I have to work hard not to quote in full. It begins the collection with an authority both daring and straight-faced:

Two seraphs in the live oak’s highest boughs are sleeping,

constructing minutely their crystalline fretwork,

a lattice of musics: the inscrutable curios of angels

in the holy bottegas of their dreams.

Grace is the only applicable word here. This poem grows more inviting and mysterious each time I read it, and describes its author’s powers at his best, “crystalline…gauzy…dappled…holy.”

Where Clark excells is in the delicate commingling of the domestic and divine, and, as the book progresses, the suburban and surreal. From pythons in grand pianos to pachyderms on parade, we never quite know when or if our dream has ended. This climaxes in the strange and unforgettable “Whatever Burn This Be,” in which a coughing fit that never stops becomes a kind of quasi-psalm: “angled properly the noise he made // this ultimate ugliness could strike the ears / of paradise in a way no prayer could hope to.”

The book ends with the longish “Reveille with Lullabies,” where, as in Donne, powers that would normally separate the lovers are transformed and used to reinforce their union. The disturbance in Clark’s poem is not a rising sun, but a colicky son, and Clark laments the child’s pain while recognizing each cry as a catalyst for new and more exquisite kinds of consolation:

You vine your melody

around him as if to leach

the poison out and make

of it a full white flower

that could lure a moth

out of the night,

a moth to drink and take

the colic off beyond

the reaches of these limbs

you vine in melody.

This poem, and many others in Reveille, is both love poem and anti-aubade; the lovers’ isolation in sleep is repaired by their reunification in wakefulness. Or at least semi-wakefulness, since the night air still seems flecked with Queen Mab’s little atomies.

But compared to the diamond-hard precision of the best of the book—“Jellyfish,” “Cradles,” and “A Stipulation”—this finale feels too fragmented, too prolix: “When we leave the house our son is crying / in his grandma’s arms we leave him crying // From our loath retreat to the old drive-in / we call home and hear his crying…” Its repetitions don’t quite accrue the gravity or shifts in meaning we keep hoping they will. The seams of sleeplessness show, and not as a deliberate concretion of its content. Clark pushes himself up to the edge of sentimentality, a balancing act that most poems worth reading risk, but in which rare missteps seem all the more disastrous: “one cry spins us like rotisseries / in the big white furnace of our bed.”

This happens every so often, a certain tone against which I keep stubbing my toe, a metaphor or simile that rankles. And there are times when the celestial comes off tarnished and cartoonish after contact with the earth. There’s the angel in “Heimlich for a Heavenly Windpipe” choking on something at a barbeque, another under a bridge spray-painting her wings. Clark’s at his best when he leaves the urge to ironize behind, and his yokings are the most compelling when distilled: “amplified fog” for white noise, “waterlogged diamonds” for jellyfish, moments in the book where “being purls and quickens as though something good / had breathed on you.”

What makes Reveille worth re-reading is the way it ushers us into a world whose gods may have dissolved but which nevertheless is tinged with sensuous, even divine, particulars; instead of angles, peahens—”backs matte gray / with speckled under-feathers—preen and strut.” In his best poems Clark consecrates unostentation, and makes what’s ordinary visible again, “a temple / to no god but itself.”