A Review of By Light We Knew Our Names

by Jaclyn Watterson

Anne Valente

Dzanc Books

222 pages

$14.95

The thirteen stories in Anne Valente’s debut collection, By Light We Knew Our Names, reside in a world where loss is easy to map—until it isn’t. Parents and children die, mothers and fathers leave their families, babies are not born, or else lose their innocence. Pain is the most reasonable thing in this world, and yet it is always, always eclipsed by wonder.

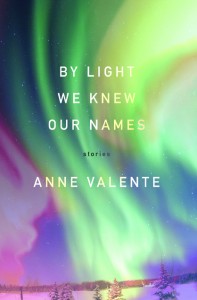

In the face of rape, the aurora borealis. With coming of age, the discovery of powers to see what few others can. Sirens in the night calling to witness mourning and the possibility of a marriage breaking up. Amidst war and the disappearance of Amelia Earhart, a sisterhood that spans generations and species.

This is the stuff Valente’s fiction is made of.

She is adept at tracing the pain of death and divorce, the wrenching of innocence from us, so that we recognize these familiar breaks, recognize our own potential to suffer what she knows. And yet, Valente insists in every story, there is more to loss than the simple fact of it. There is the natural world, and it is glorious, splendid, and every bit as harsh as the beauty of human relations:

So begins Valente’s title story, “By Light We Knew Our Names.” The story is set in Alaska, and the northern lights refract the physical and emotional pain of the violence of a man’s world where girls are treated as less than human. But Valente’s girls respond to the impossible pain of rape their community refuses to acknowledge, incarceration by boyfriends who “play rough,” theft by fist-wielding fathers, and other unspeakable violences by emerging as more than human—by holding each other up to the light.

This is what Valente does with her characters, and to her readers: she shows us the pain, but also the transcendence we are all capable of. She reminds us that beyond the pain, there is always light.

Valente notably achieves this effect in several stories with her exquisite renderings of first-person plural narrators. In “Dear Amelia,” a stunning sort of love letter to Amelia Earhart, Valente writes, “We might have accepted this, Amelia. We might have grown to love our double lives the way our mothers learned to accept theirs, all the secrets they kept, a power they held against bone, a protected full-house hand.” In this story, we feel the pain of separation, that “we” can never be “them,” that no matter how we love our mothers or our heroes, we can only, at best, approximate being them. But this separation is equally cause for celebration—that there exists a “we,” that we possess the incredible potential of collectively experiencing the world, and narrating our place in it.