American Psalm, World Psalm by Nicholas Samaras

a review by Andrew Wells

The Ashland Poetry Press

2014

$22.95

Nicholas Samaras’ second book, American Psalm, World Psalm is a work of biblical ambition. In addition to his title, Samaras invites comparison with the 150 Psalms of Jewish and Christian scripture by numbering the 150 poems in his collection as 1st Psalm, 2nd Psalm, etc. Of course, no poet can hope to compete with the Bible’s collection of lyrics which still inspire the faithful after more than 2,000 years, and even translating or imitating the Psalms sets Samaras’ work up against some of the greatest writers in English, including Wyatt, Sidney, Herbert, and Milton who all wrote psalms.

However, Samaras has captured some of the spirit and music of the biblical Psalms and made them sing again, even in an increasingly secular age. He writes in an introductory note that for him, “music was always built into the very word psalm,” and he has tried to “render [it] in contemporary times, filtered through the soulful structures of American music, in blues form, jazz form, folk, modern pop, and hip-hop form” while staying true to the “base form” of the Psalms, “illuminating what may be constant in human struggle.”

Several poems make good on the promise of musical form and rhythm such as “Psalm in a Blues Progression,” which contains one of the funniest moments in the collection:

I know my God is not dead.

Sorry about yours.

I know my Lord is not dead.

I’m genuinely sorry about yours.

I just recognize any power beyond myself.

Beyond ego, there’s always something more.

In “Psalm as Musicology” we find some of the rollicking rhythms and rhymes of jazz or hip-hop:

hearing the treasure of the pleasure in syncopated leisure,

singing blood flow, let’s go, shiver in arpeggio

There are also rhymed and unrhymed and tetrameter sonnets, antiphonal songs of call and response, and riffs on calypso and rebetiko music. However, most of the poems in the volume take deceptively simple forms in short two to four line unrhymed stanzas. Samaras’ voice in these verses is earnest and confessional, often speaking about his beloved father, Kallistos George Samaras a notable Greek Orthodox priest and theologian. In “God of My Father Kallistos,” he writes:

Conjoined, ontological, my love for my father

is my love for the Lord, my parent who directed me

always there. A man who loves his father loves the Lord.

Samaras is also serious when he writes of his deceased “children in heaven” and of his own depression which he calls “a mild form of anger,” a “struggling to get from black into gray.” He finds healing for his deeply personal pains in his faith and his religion. At a time when many Christian groups have become progressive, Samaras defends his traditional beliefs:

Lord, these years, it isn’t popular

To talk about “sin.”

God is a loving God who will

Love us “just the way we are.”

Other denominations have an easier God.

But my God is Orthodox and calls me

To account for my every breath.

Breath is a recurring theme throughout the collection. It is the title of the first of the five sections or “books” of 25 or 50 poems, the others being “Petition the Lord,” “Movement,” “Gratitude, the Father of Praise and Humility,” and “Stillness.” Samaras writes that he wants to “Aspire the Lord and exhale myself,” so that “Every breath in is gratitude. Every breath out is fear.”

This collection is full of somber laments for the lack of contemporary spiritual life and calls for revival. Samaras answers objections against God, writing that “We’re not fair to God, either.” He talks of being persecuted for his beliefs by young Croatian communists in “The Political Psalm”:

In the city of Knin, I was biblically stoned

for the crime of walking down the street with a priest

…

Now, I believe everything is political.

Choosing to live is political.

Believing in God after the Holocaust is political.

Samaras does not shy away from politics in his poems, writing in “Against Political Correctness” that

I will not feel embarrassed for my faith.

I will vote my conscience, call abortion

murder, not choice—

…

I am sick of cheap divination

and petty superstitions, the hurt

feelings of anyone else, the multipluralistic

quagmire of America.

Move on to the real.

Name God.

Open to the fact.

Samaras’ dream is a new era of spirituality in America. In his longest poem, the 119th Psalm, he writes that

The American Psalm can become

the world psalm again. For America holds

the world in itself—holds a home for the world.

We just have to remember

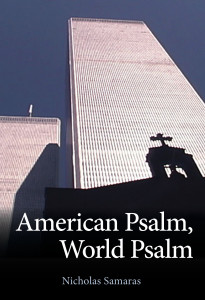

The cover of the book is a photograph of the shadow of a cross cast by an Orthodox cathedral against the towers of the World Trade Center, and it seems like part of what Samaras wants his readers to remember is the spiritual revival and feeling of unity after 9/11/2001. Looking at the cover image, readers may be reminded of the cross of twisted metal that construction workers found in the rubble and set up as a shrine. That cross remains on display in the September 11th Memorial and Museum despite a separation of church and state lawsuit. Although Samaras’ book may not fulfill all its biblical ambitions, if he can help his readers remember, he may count it as a victory.

Andrew Wells is a Ph.D. candidate studying British and American literature at the University of Utah. His research focuses on the Protestant culture of translation in Renaissance England, especially the strange ways in which Puritans came to translate the bawdy tales of ancient Greek and Roman literature.

Andrew Wells is a Ph.D. candidate studying British and American literature at the University of Utah. His research focuses on the Protestant culture of translation in Renaissance England, especially the strange ways in which Puritans came to translate the bawdy tales of ancient Greek and Roman literature.