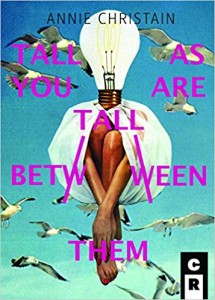

Tall As You Are Between Them

by Annie Christain

a review by Dorothy Chan

C&R Press

2016

117 pages

ISBN: 978-1-936196-61-6

Annie Christain’s debut collection, Tall As You Are Between Them, is a stunner. Christain’s whole book is a trip, an out-of-body experience that’s filled with B-movie titles such as “A Spider-Man Must Be Born of This Earth,” “Marilyn Monroe’s First Miscarriage Lives on Colfax Avenue,” and “Xennials.” Christain speaks to our greatest fears; she places us in an alternate post-apocalyptic universe where the speakers may turn to religion and spirituality but are inevitably doomed. And yet, Christain lifts us with her vast array of knowledge—I admire the hodgepodge of historical information that the poet offers. Christain transforms the protest poem, the persona poem, and the unity of a collection.

“Mayfly Satellites” is the beginning piece that truly propels the collection forward not only through the out-of-body experience, but also through the speaker’s questioning of where to go when one is transported back to a society that’s fallen apart:

This is the town where I imagined myself

in your bed

holding the You Are Dead sign

I stole from the Out of Body Experience hospital,

where the electrical stimulation to my brain

gave me the sensation of being hugged (9).

Christain gives us both simulation and stimulation in this sci-fi version of Rip Van Winkle. We get a mayfly time lapse as the speaker recalls bits of history: news segments flickering in the television of the mind, the “abandoned cotton gin,” “the burning gas field/set on fire by the Soviets forty years ago,” “your bedroom exactly as it was in 1974,” etc. (9-10). Despite the coldness of the alternate reality, the speaker still grasps at love:

I mean so I can be near something you touched.

I’m getting closer to receiving

what a wrongly imprisoned god deserves (11).

If Christain’s titles are something to behold, then her last lines deserve just as much applause. “What a wrongly imprisoned god deserves” is the sentiment that guides the entire collection. On a related note, Christain follows “Mayfly Satellites” with “God Wants You to Go to Jail” and “The CD Mr. X Gave Me That Proves Everything I’m Saying Was Confiscated by the Police upon My Arrest and Sent Directly to the Ethics Department which both arguably transform the persona-protest poem. The prose form of “God Wants You to Go to Jail” adds to the newsreel-protest element of the piece. Christain’s lines hit: “He created us because the doctors have to know how to treat injuries in the combat zones of Iraq/and He was scared of us, Jesus Christ.” The “Jesus Christ” adds a lot of emphasis—we get Christain’s awareness and dark humor as she makes her poetry more relevant than ever:

There was a god who told you to riot. He made the last hour with a strand

of your hair. Listen. He made the White and Black protestors yell at each

other at the Central Park Five trial, all holding signs written in the same ink

and handwriting, all wearing ear pieces connected to the same god (12).

“The CD Mr. X Gave…” is a strong complement to “God Wants You to Go to Jail.” While the poet uses a prose form in “God Wants You to Go to Jail emphasize the gravity of the piece, she uses carefully constructed delicate lines in “The CD Mr. X Gave…” to bring out a different tone of protest—a tone that shows the gradual nature of protest with a thought by thought breakdown. Christain ends the poem with a set of lines that really speak for themselves:

I’m a warrior

and if you don’t decide to make this handsome

face a free man,

I’ll fuckin’ kill myself (16).

Each of Christain’s lines stand on their own, and her enjambments lead up to the finalizing emotions of the poem: “I’ll fuckin’ kill myself.” And behold: the poet is not afraid to give it all away, once again proving how a lack of restraint is the best thing that can happen to any poem.

“Under John Wayne’s Hat” is such a smart, standout poem, in which “Stalin and John Wayne play mancala and eat fish with each other as much as time allows…” (34). Again, Christain educates her reader—I became so fascinated with John Wayne’s peace role during the Cold War. After setting up the poem in a dream-like sequence, Christain ends with:

After several hours of contentment, they are hungry and sick of Mangala.

The Cold War begins again like it always has, and when Americans see

themselves under John Wayne’s hat,

it’s such a relief (35).

With the ending lines, Christain highlights Wayne’s peace role. She also cleverly brings the hat mentioned in the title to parallel final line, giving the reader an image of Americans hiding under John Wayne’s hat. It’s images like these that balance the manuscript out—as much as Christain is writing about dark times, she injects enough quirk into her writing for the audience’s imagination. Perhaps, Christain is creating a bizarre collage for us—and on a side note, it’s definitely a collage that fits the beautiful artwork on the cover of her book. For instance, in “Pretending to Go and Come from Heaven by Fire,” Christain gives us: “and carved: NASA is Babel” (44). And with this line, right away, I get the image of Bruegel the Elder’s The Tower of Babel. Christain is a poet who knows her references and more.

The second section titled “The White House Tapes” is the heart of the collection. I love the poet’s multiple persona approach. “VI – Alexis Hophauf” and “XXIII – Margaret Hophauf” are the two standouts for me. An added bonus is how the two poems connect. Alexis’ “Diana” seems to be related to the Diana of Roman mythology, the goddess of the hunt: “One night as I was flipping through the television channels, Diana pointed at the wrestlers bouncing off the ropes and said: Those people look just like my people” (54). And yet the Alexis Hophauf persona poem ends curiously: “With Diana, all I could think about was Cassiopeia” (54). And here Christain gives us a juxtaposition: a woman with is like Diana of the hunt, but like Cassiopeia in her beauty.

For me, Christain’s poetic femininity really comes out in Section III, first in “All your Best Key Chains”:

and you’re a girl too, don’t forget,

and the more you thought about it,

the more you realized that in 1992

when you watched the episode of Picket Fences

where Kimberly’s best friend spent the night

and suggested they kiss,

but when they did,

the censors blacked out the screen,

and you wondered: What girl would I kiss if

I had to and would the world black out?— (78).

This sensuality continues in “Inside a Hand Basket in the Burlesque Theater,” which contains the title within the poem:

and the granite-encased monoliths

of your muscular legs

drilled to the sides of the stage

are as tall

as you are tall between them (83).

Christain gives us such a beautiful motioning and bizarrely sexual nature in this title poem. She brings out her strength of both repetition and emphasis. I love how this last section is a culmination of all the poet’s strengths: B-movie titles, last lines with a kick, specifics that are on repeat, and sensuality that becomes entwined with the poems’ movements. Yet, underneath it all, Christain’s weird still takes the forefront. For instance, in “Marilyn Monroe’s First Miscarriage Lives on Colfax Avenue,” the poet first presents an epigraph that describes the “Marilyn Monroe Velvet Rope Musical Water Globe.” It’s like the poet is in a tongue-and-cheek way, presenting the bizarre in both the miniature form of the snow globe (and by extension, the epigraph), and the macro level of the poem (and the context of the whole collection).

Finally, Christain ends Tall As You Are Between Them with a bang: “Al Supercomputer as Black Magic Megaritual Amplifier: Sir Paul McCartney’s God Given Right.” Once more, Christain’s speaker guides us through a poem with a faster tempo:

Good characters can only die if it advances the plot.

Once more in a faster tempo (118).

And with that, Christain takes us through one round that probably demands another.

Dorothy Chan was a 2014 finalist for the Ruth Lilly and Dorothy Sargent Rosenberg Poetry Fellowship and a 2016 semi-finalist for The Word Works’ Washington Prize. Her work has appeared or is forthcoming in Blackbird, Plume, The Journal, Spillway, Little Patuxent Review, and The McNeese Review. Her poetry has been nominated for a Pushcart. She is the Assistant Editor of The Southeast Review. Follow her on Twitter: @dorothykchan