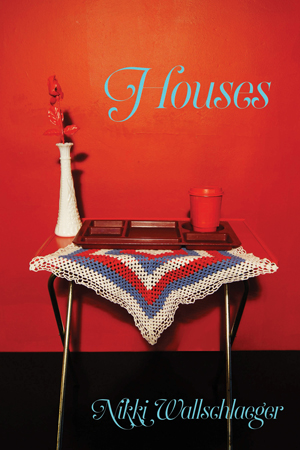

Houses

by Nikki Wallschlaeger

a review by Brandon North

Horse Less Press

2015

82 pages

ISBN: 978-0-990-81393-4

Nikki Wallschlaeger’s first full-length book of poetry is most animated by this question: “Can I understand?” Not whether one does understand, but whether understanding is actually possible. Readers enter into intimate spaces—houses—filled with utterances that work to alienate any one subjectivity, to position each reader as “an estranged somebody,” so that they are dissuaded from wagering any framework of meaning as essential to understanding the poems. As a result, any meaning drawn from the poems is countered by a productive anxiety about understanding gained by language.

The prose-poems in Houses are in sections that function as different rooms the reader moves through (each has “house” in the title). In early poems, anaphora often begins each section—like the phrase “As a westerner” in “Yellow House”—to indicate that although sections are connected, it is a somewhat arbitrary connection, much the way rooms are adjacent but have very different assumed uses (bathroom vs bedroom). Though prose sections might welcome a reader at first (no lineation might signal easier/faster reading), the logic of the voices contained in each house-poem jars expectations of intended meaning when moving between sentences. The blurry line between host and guest is explored, as readers are drawn into an immediate intimacy with each poem’s voice(s). As guests/strangers (over)hearing these utterances, readers try to grasp the obscured logic of language in poems like “Marigold House,” for example, which states in one section “We’re still figuring out how we got here. A song from an 80s supergroup says the same damn thing. It’s a real pleasure to meet you” and then, by the next section, states “I recently figured out how I can tell when someone is trying to pull rank. They either shorten your name or pretend you don’t have one.” These voices alienate the reader because there is no consistent effort to structure the logic between the sentences of each poem, despite the voices using specific, intimate tones and phrases—as with a line like “He was such a rotten President, a dark of overconfidence, pizza vomit.”

In the effort to increase a reader’s sense of alienation, the poems’ titles gain more specific colors that in turn produce more specific logic and tone to the voice(s). As the colors shift from relatively objective ones, like “Pink House” and even “Mint Green House,” to relatively subjective ones, as with “Sable House” and “Willpower Orange House,” the increasingly subjective colors also correspond to increasingly subjective utterances, ones that become less and less concerned with framing the poems. This movement toward the subjective is clear when comparing sentences in earlier and later poems. “Black House” states:

Compare this to “Artichoke Green House,” a later poem, which states:

In “Black House” there is more interest in framing the utterance for a stranger/guest, whereas in “Artichoke Green House” the voice is more like a stream-of-consciousness of associations and declarations that a reader becomes suddenly intimate with, or even inhabits—a guest merging their consciousness with that of their host’s. With transitions between sentences like “Has nothing to do with you. I was going to say” happening more and more, Wallschlaeger’s poems increasingly seem like an amalgamation of voices speaking/not speaking to each other, understanding/not understanding each other. This dynamic is also refracted out to exist between the text and the reader; the text speaks and doesn’t speak to readers, they do and don’t speak to the text. The exchange goes on, but the meanings from/within the exchanges are increasingly opaque. Though the intimacy with the voice(s) increases as the house colors become more subjective, this actually increases a reader’s alienation; the closeness to the host voice(s) heightens the guest’s fear that they cannot understand the host because the separateness of their consciousness is reinforced by the lack of framing around the host’s utterance.

As the poems’ logic becomes more obscured, a reader must lean on the colors in the titles as guides for understanding, as they provide the most obvious framework. But this reliance on color throws into a relief a racial/ethnic subtext beneath the search for understanding. As a reader frames meaning with a color, there arises an anxiety about classifying a specific color because of potential meaning(s) that might be attached to the color. Think of the identification problem that comes with creating a color scheme and being unsure if a color is, say, more red or orange. This anxiety about colors having certain attached meanings in turn produces an anxiety about matching up voice(s) in each poem with specific racial identities. But this anxiety is productive. By worrying over attaching meaning to these poems based upon a superficial context (color as frame), readers can intuit that because each person has their own subjective impressions, one must not be so quick to assume that they understand another, nor to quickly affix meaning to another’s communications—especially when considering the possibility that complete understanding isn’t possible.

In the collection’s last poem, “My House,” the voice is unified through the return of anaphora, which is used to begin fragmented phrases rather than sections. This poem’s voice only ever speaks by saying they are “holding” something: “Holding Mammy’s red petticoat,” “Holding hostis,” “Holding what I’m really saying.” But despite this voice’s unification—this voice that may both possess and be possessed by things held (like the reader/guest/“hostis”)—readers must still acknowledge that subjectivity may prevent them from understanding how the relationships between what is held define the voice’s reasons for holding them. Because this last voice is only unified by defining itself through things held—embraced but not necessarily incorporated (completely) into a body—if a reader does feel embraced by the voice, if they feel it is “my house,” too, this doesn’t necessarily indicate that understanding is transferred between host and guest. “Holding what I’m really saying” can indicate that the voice is holding their own subjective meanings back, keeping some things in private sections of the mind/home, never taken out to face the rupture of understanding.

In this final poem, meaning becomes displaced in favor of the proximity of physical things. And because there is no fixed meaning to the gesture of holding, Wallschlaeger’s last poem leaves readers with the sense that there is also no fixed meaning to the gesture of poetry, whether or not it makes a reader feel alienated. In Houses, the anxiety of understanding, especially as it pertains to how people are Othered through racial and/or ethnic difference, is productive precisely because it ultimately pushes the reader toward active embrace, toward holding—in spite of the possibility of prejudice. To quell the anxiety of understanding, these poems say, we do not need access to someone’s meaning so much as we need an intimacy with the voice(s) that live the resulting consequences of their meaning—consequences that happen partially because of others’ attempts to make meaning of experiences that aren’t their own.