Lindsey Drager

Mammoth Grief

I.

The elephant occupies the full span of the screen and then some, its mass cropped by the frame. Wires through which electricity will run connect in webs around her. She is in every way entangled: in progress, revenge, and moment. This is an execution. This is a punishment for ending three human lives. A hanging had been considered, but science stepped in. This is January, 1903. This is more about the beginning of electricity than about the end of an elephant.

The moment of detonation surprises the viewer. It passes too slowly; there is no jolt or shock, just the commencement of fall. Then smoke plumes fill the screen, though it’s clear there is no fire. It is the beast’s insides being consumed by mechanized heat.

What I find most poignant is the fall: that great mass toppling head-first toward down, the landing so fully unnatural, like the dropping of a plastic toy.

II.

“Elephant, beyond the fact that their size and conformation are aesthetically more suited to the treading of this earth than our angular informity, have an average intelligence comparable to our own. Of course they are less agile and physically less adaptable than ourselves—nature having developed their bodies in one direction and their brains in another, while human beings, on the other hand, drew from Mr. Darwin’s lottery of evolution both the winning ticket and the stub to match it. This, I suppose, is why we are so wonderful and can make movies and electric razors and wireless sets—and guns with which to shoot the elephant, the hare, clay pigeons, and each other.”

— Beryl Markham, West with the Night (1942)

III.

Because to execute means both to finish and to carry out, I find myself possessed by this film. It is before this short clip and all its implied devastation that I place myself when I think about what it means to be an adolescent, that murky, twilight space that marks the not. Not child, and also not adult. A cleave in the contours of the time-being, both the place linking one age to the next and the place denoting where our age divides. Or, to correct the geometry of the image: because our frames are vertical, because our brains and our bowels live on the same upright plane, it is perhaps more accurate not to consider our trajectory forward but down, such that we are always withdrawing, age like gravity insisting we contract, a system less like coming to the end of a road and more like the collapse of a machine, our synapses snapping and flickering—all electricity and execution—until we lay our bodies down, where brains and bowels live on a horizon extending infinitely without endpoints. In this way, we escape the where and when of end.

IV.

I cannot come to explicate this short film because I cannot overcome a first question that lingers in the dusty, rusty corners of my mind. Instead I resort to narration, to locating and harnessing the story rather than disclosing a catalog of fact. But I wonder if anyone could objectively unfold this, considering we are each a little bit at fault for crimes committed in our youth, for butchery in one form or another, whether as flesh or idea, for a spectrum of inventive deaths. I cannot come to explicate because I cannot answer that first question, which starts with the birth of an elephant, with the moment the being exits its mother and where that birth takes place. What I need to know first has to do with the rhetoric of zoo, with childhood memories of the great caged beings adorned with strange abrasions on their skin, the skin shrunken and shriveled like the paper of an unused cigarette left overnight on the lawn, left to absorb autumn dew: puckered, wrinkled. Narration: Once there was an elephant who was fed a lighted cigarette. Imagine the lit bit sitting in the pit of the gut. What method would the body use to rid itself of the thing so full of error? Can we blame the beast’s response, that is, to end the person who lifted the cigarette to the elephant’s lips and pushed it down the elephant’s throat? It was more the body’s response to a foreign event than a crime. And herein lies the first myth of sacrifice for progress. I gather these thin threads of story; I member and remember how it goes: the child, the zoo, and an elephant, that great mass some distant brand of magic. And then amended: experiments in how best to end each other and at the center, Topsy toppling after currents of electricity coursed through her giant frame.

V.

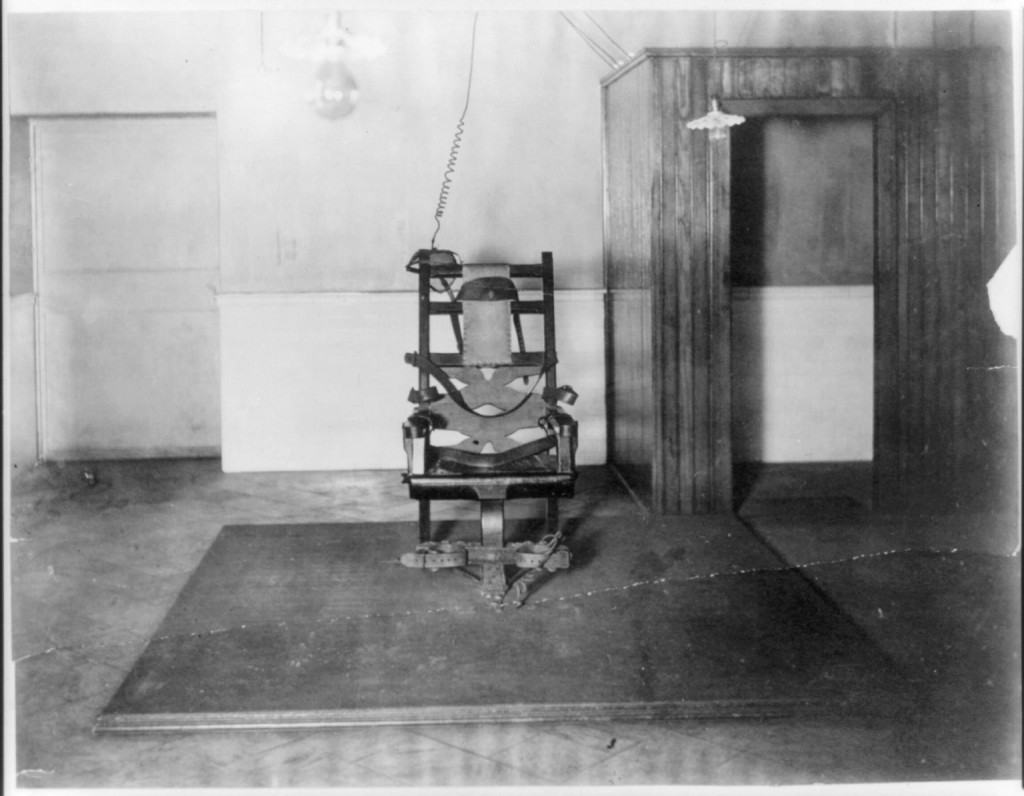

Auburn State Prison, 1908

VI.

What I need to know first—what I cannot find in the archive of story told wrong: what child’s hand fed the elephant those carrots laced with cyanide before they let the current flow?

Lindsey Drager’s fiction and creative nonfiction has been published or is forthcoming in Mid-American Review, The Journal, Sonora Review, The Pinch, Zone 3, Gulf Coast, West Branch Wired, Black Warrior Review, Cream City Review, Kenyon Review Online, and elsewhere. She has received residency fellowships from the Kimmel Harding Nelson Center for the Arts and the Vermont Studio Center, and was most recently named a finalist in the 2013 Sarabande Books Mary McCarthy Prize and the 2014 Miami University Press Novella Competition. A PhD candidate at the University of Denver where she edits the Denver Quarterly, her first novel, The Sorrow Proper, is forthcoming from Dzanc Books in 2015.

Lindsey Drager’s fiction and creative nonfiction has been published or is forthcoming in Mid-American Review, The Journal, Sonora Review, The Pinch, Zone 3, Gulf Coast, West Branch Wired, Black Warrior Review, Cream City Review, Kenyon Review Online, and elsewhere. She has received residency fellowships from the Kimmel Harding Nelson Center for the Arts and the Vermont Studio Center, and was most recently named a finalist in the 2013 Sarabande Books Mary McCarthy Prize and the 2014 Miami University Press Novella Competition. A PhD candidate at the University of Denver where she edits the Denver Quarterly, her first novel, The Sorrow Proper, is forthcoming from Dzanc Books in 2015.